The Story of Sainte-Marie among the Hurons Part 1

It seems fitting to have a gathering of living history and museum professionals visit Sainte-Marie among the Hurons in Midland Ontario Canada in June 2019 for the annual ALHFAM conference and annual meeting. Just as in days of old, we bring together groups of people for one common goal: To experience and learn from one another and share our common interests and expertise in the world of museums, living history sites and farms, be they small or large.

Sainte Marie was founded in 1639, 380 years ago, on the shores of Georgian Bay, and it became known by the French Jesuits who founded it as “A small piece of France in the wilderness.” At its peak it housed within its palisaded walls a grand total of 66 French men, many of whom were laborers with little to no education and a very small chance for a good life in France.

The New World was chosen by these men for many different reasons, including the opportunities for adventure and a better life. However, the most important reason was a very strong belief that the French Jesuits were doing a holy deed by being among the Huron Indians, teaching them a very different belief system. Through their conviction they built a wooden fortress in which the Jesuits could feel safe and in which each could call home.

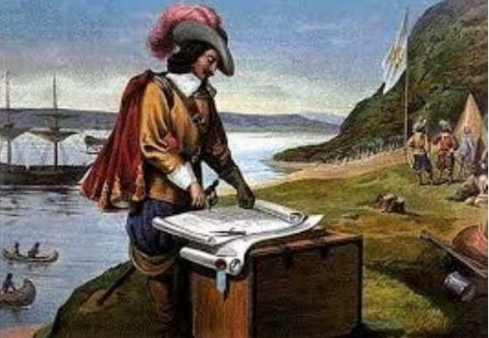

But the story starts much earlier. In 1609 adventurer Samuel de Champlain, the first European to explore central Ontario, found himself in the land of the Wendat peoples, a confederacy of five tribes that numbered near thirty thousand by Champlain’s reckoning.

Champlain was able to form alliances with the Wendat, Montagnais and the Algonquin peoples, who eventually would help to win major battles against the Mohawk.

Champlain made many trips across the Atlantic and soon brought four Recollet priests– an order of the Franciscans–to the territories, and they began the missionary chapter of this story.

One of the best-known of the Jesuits to come to this part of Canada was Jean de Brebeuf. Born in Normandy France in 1593, Brebeuf first came to Canada in 1625, where he worked with the Wendat for the rest of his life until his death in 1649.

It was Brebeuf who was able to create and write a French/Wendat lexicon for the use of other Jesuits in their work of bringing Catholicism to the Wendat people.

Brebeuf and the Jesuits spent untold hours writing what was and is known as the Relations, a form of diary, that was sent back to France. In these narratives are found a great resource for the ethnography of the Huron/Wendat peoples. Without these diaries we would not have the wealth of information that we do today.

Through the many trials and tribulations that were experienced by both the French and Wendat, there are many exceptional stories of life in New France. Robert le Coq, the first donné – a volunteer who signed a contract to work as a business agent for the Jesuits in return for food, shelter and clothing—kept the mission supplied with everything needed to run it. Robert accepted many gifts of fur from the Wendat and in turn took these goods to Quebec to barter for everything from iron for the forge to linens for clothing.

Robert made many trips to and from Sainte-Marie to Quebec for supplies, and it was on one of these journeys that a very dramatic event took place. Traveling with a group of Wendat from Quebec, Robert became ill with smallpox, and they left him for a dead on a small island. As his body became covered with sores and pustules, he managed to find shelter there, and he eventually recovered. Not long after his recovery, a flotilla of Wendat came by the island, he convinced them of his identity, and he made his way back to Sainte-Marie. Imagine the surprise of the Jesuits, his colleagues, and those living at the mission who, having mourned his death, saw him miraculously reappear among them!

The mission headquarters in 1639 was the center of French life in the New World. Not only did the Wendat visit in large numbers, but the northern tribes also came to Sainte-Marie to trade with them. These northern tribes used the location as their temporary residence because its location was close to the vast majority of Wendat villages in the area, making trade much easier.

As buildings at Sainte-Marie began to rise, so too did the French population, including a cook, a farmer, a blacksmith and a carpenter. Jesuits, donnés, paid workers, soldiers and a number of young boys in their early teens lived at Sainte-Marie. The Jesuit priests could be found at various villages of the Wendat on any given day, conducting services and teaching/preaching Catholicism with the help of various donnés.

Stay tuned for more!

Contributed by Del Taylor, 2019 ALHFAM Annual Meeting Conference Chair